21st Century Retirement Education

(to navigate the complexities of modern retirement planning, moving beyond traditional approaches to address the unique challenges facing Gen X and Baby Boomers

Live in the Austin area?

Attend one of our Retirement Education Seminars at Concordia University, Texas

Join us for this exclusive seminar crafted specifically for Generation X and Baby Boomer professionals. While saving during your working years might seem straightforward, transforming those savings into lasting retirement income is a complex challenge that many Americans, including numerous financial professionals, struggle to manage effectively. Space is restricted to guarantee personalized attention.

At GoDialRetire, our expertise lies in conducting retirement education seminars and offering personalized coaching. We tackle the intricacies of modern retirement planning with innovative strategies that address today’s unique challenges—far removed from the retirement scenarios our parents faced.

Hosted by Wealth and Retirement Coaches Charlie Dial and Cort Dial, Founders of GoDialRetire

Only 20% of Americans Have a Solid Plan

Only 20% of Americans possess a comprehensive retirement plan. Among that small minority, 96% express confidence in having sufficient retirement income.

Customized Financial Strategy

(includes taking advantage of tax-efficient withdrawal strategies, minimizing risk, and optimizing Social Security benefits)

Maximized Retirement Savings

(designed to ensure that your retirement savings are optimized to support you throughout your retirement years)

Adaptability to Life’s Changes

(so you're prepared even when the unexpected occurs.)

Long-Term Relationship

(we'll be here throughout your retirement journey and supporting your family when you are gone)

By partnering with us to help develop your retirement plans, you’re not just preparing financially for the future; you’re taking a proactive step towards creating the retirement life you’ve always envisioned.

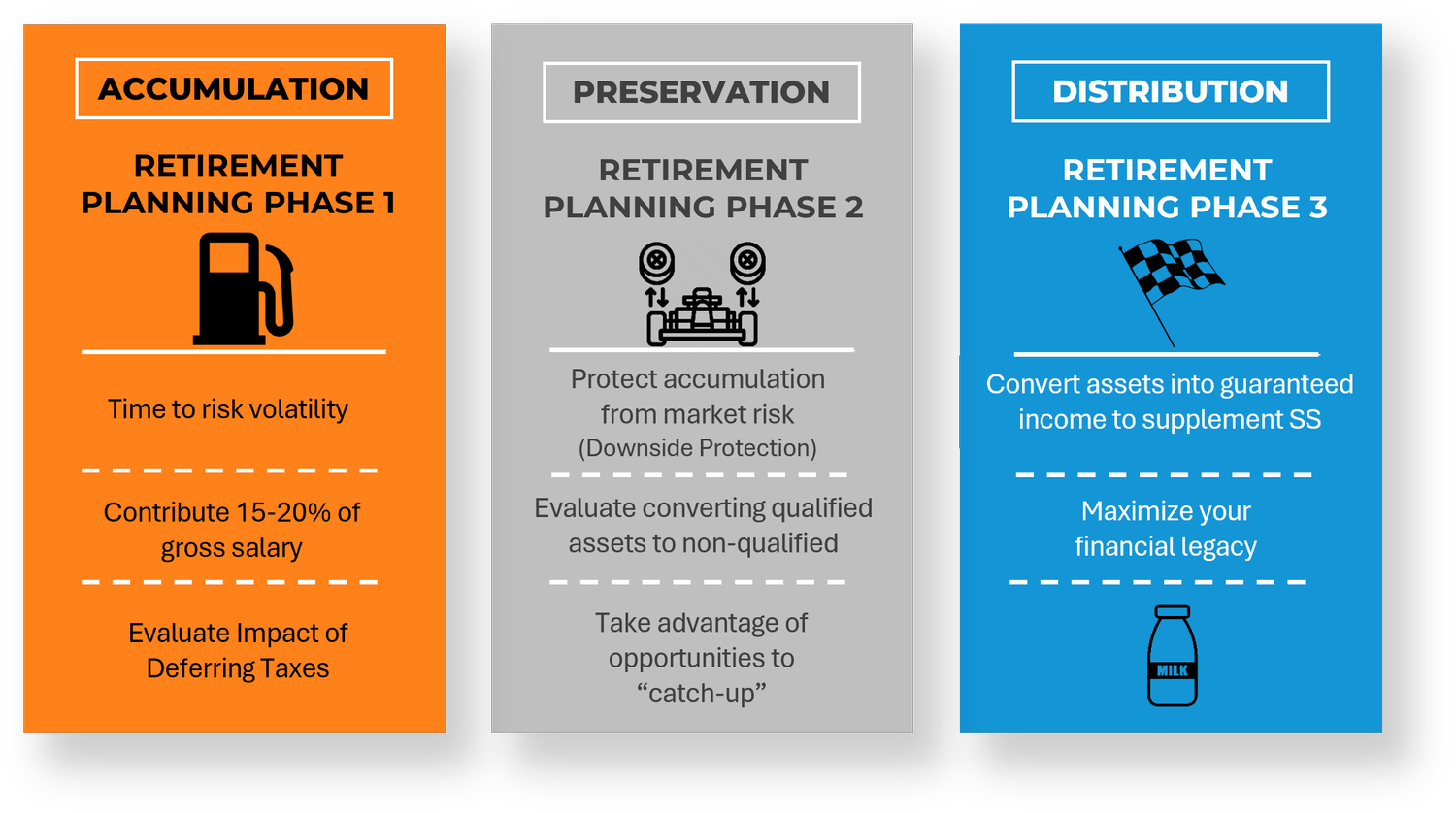

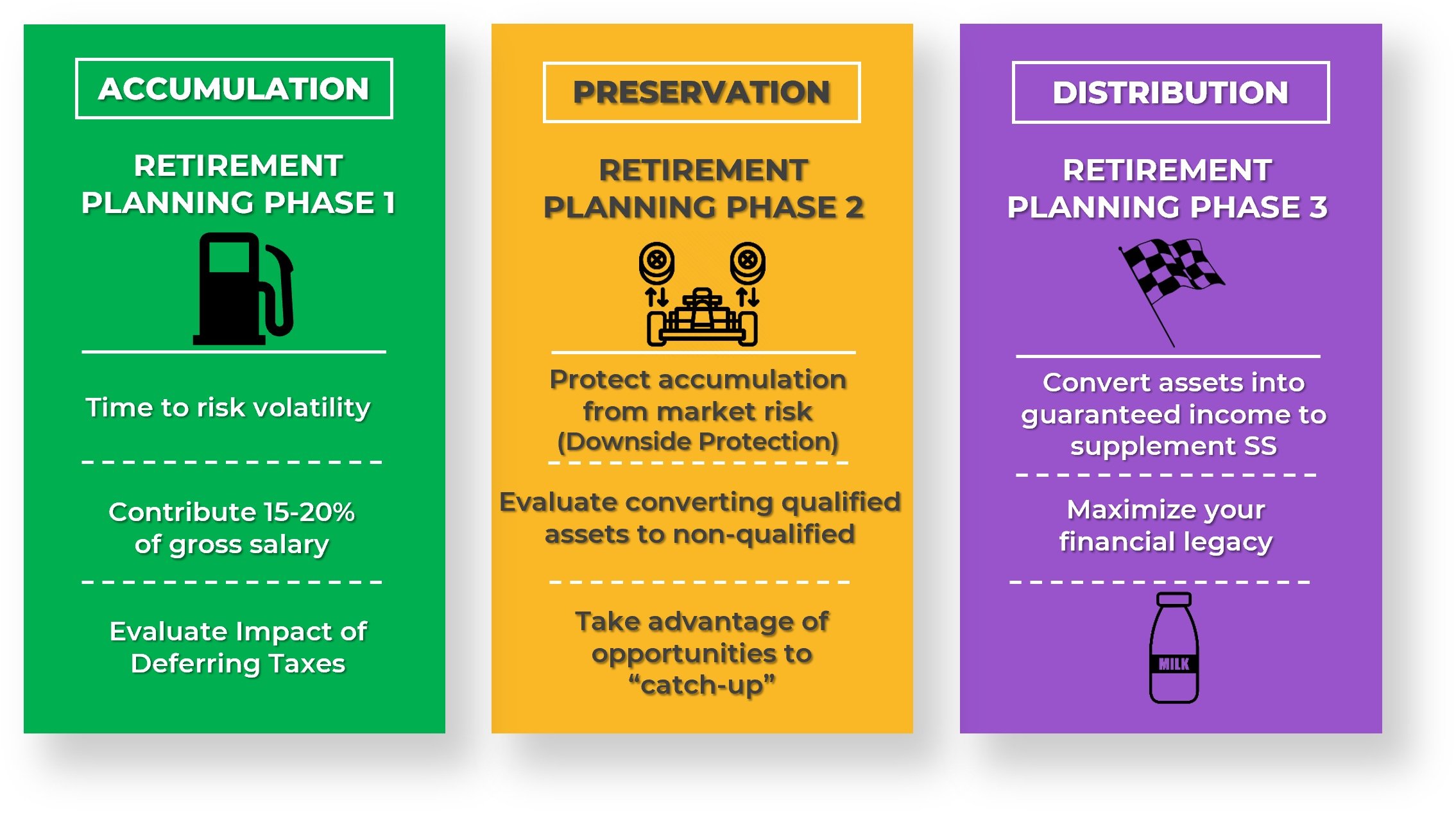

“Future-Proofing Your-After WorkYears”

Meet the Retirement Coaches

Co-Founder

Licensed Agent and Retirement Coach

Three plus decades of coaching top-tier executives globally

Author of the acclaimed book Heretics to Heroes, A Memoir on Modern Leadership

Cort Dial

Co-Founder

Licensed Agent and Retirement Coach

Graduated Summa Cum Laude from Concordia University, Texas, with a degree in Psychology

Charlie Dial

Cort and Charlie, alongside Cort’s son-in-law and Charlie’s sister, Trent and Katy Reynolds, are the founders of Trent Reynolds Player Development (TRPD) and serve as dedicated coaches.

At the core of TRPD lies a mission that goes beyond the game: "Develop Great Players Into Great Men." This statement captures their commitment to enhancing athletic skills and fostering personal growth and character development in their players.